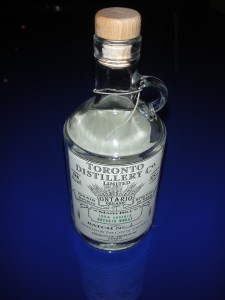

Just before Christmas, a man came to my door. He had the most splendid, waxed and curled, Dali-esque moustachios I have ever seen, was impeccably dressed, and he handed me a half-bottle (375 mL – 50% abv) of “Ontario organic grain spirit.” It was Batch No. 1 from the newly founded Toronto Distillery Co. and all he asked was that I taste it and, if I saw fit, write about it in my blog. Prominent on the label was the information that this was distilled from pure Ontario wheat. I looked up to ask him about that but he was gone. My porch was empty.

Now weeks have gone by. I have watched the level of liquid slowly go down in the little jug-shaped bottle. Yes, I have had a hand in that particular process. I’ve been trying to think of what to call this disarming spirit. Nowhere on the label does it mention the word “whisky.” I have heard it referred to as moonshine – or as “gentleman’s hooch” – but I have taken to calling it whisky. What I love most about it is the way it honours the grain from which it was made.

Often over the years, I have visited important distilleries in Scotland and Ireland and asked about the barley that went into the maltings, hoping for long disquisitions on local farming and particular heritage varieties, only to be frowned at and hear the question dismissed. Perhaps the purpose of that year’s media invitation was to write about oak casks, or peating, or the peculiar shape of the beloved pot still, or the number of times the spirit was distilled – anything but the grain itself. Which always led me to believe that what arrived in those dusty sacks (or in the vast mobile hopper, more likely) was almost incidental. Ditto the water used to make the wort or to dilute the spirit from cask strength to something they could sell more readily in the bottle. Sure, the distillery is in Brigadoon – or in Tir Nan Og itself – but when the bottling is done in a Glasgow suburb and regular Glasgow water is being used to dilute the spirit down to 40%, the whole “pure local highland sun-kissed granite-filtered sporren-blessed water” thing is best left unmentioned. The truth is not going to resonate with denizens of the Romantic Republic of Whisky.

I don’t mean to sound cynical. Marketing anything is hard work – even something with as vivid a natural back story as whisky. I guess where this is leading is that it’s a treat to come across a product that doesn’t really have a built-in angle. The Toronto Distillery Co.’s first product is what it is – a pure spirit from the first new distillery in the neighbourhood since 1933. Taste it. See what you think. Some will love it; others will hate it. I don’t think shrugging indifference is ever going to be the response to this white wheat whisky: it has far too much character to engender nonchalance.

Let me say now, I think it’s excellent. I have drunk a great many amateur spirits in my time, from the poteen we bought in milk bottles from a farmer that teenaged summer beside Lough Corib, that we ended up using to light the fire in the chilly morning because we were afraid it would make us blind or dissolve our insides, to some sublime grappas distilled by more careful unlicensed artisans in Venezia Giulia. More recently, I’ve been disappointed by “white whiskies” made in North America, mostly because they are really just so-so, wood-aged whiskies radically filtered to strip out all their colour – a process which also takes out most complexities of aroma and taste.

Quick refresher: just because a spirit is colourless doesn’t mean it’s characterless. Vodka is so ghostly because it has been distilled umpteen times in a continuous still and then filtered umpteen times more. Gin isn’t like that. Neither is whisky straight from the still, if it’s a cantankerous and inefficient old pot still that hasn’t done a very good job of purifying the alcohol, that has included all sorts of extremely complex aromatic molecules derived from the fermented grain, and sent them through the condenser. Why, friends, that colourless liquid will be as perfumed and as flavoursome as eau de Cologne – and all those aromatics come from the grain in the mash bill and the yeasts that fermented it. But especially the grain.

The two guys who operate the Toronto Distillery Co., both 31-year-old Toronto lawyers, one called Charles Benoit, the other Jesse Razaqpur, both amateurs in the best sense of the word, understand this. Because they weren’t prepared to wait a decade for their nascent spirit to mature in oak, it was imperative that they found some good honest grain to ferment and distil. They said no to barley and rye and corn, the usual grains for the making of whisky, and instead chose to work with organic local winter wheat, grown by Mike and Bonnie O’Hara on their farm in Schomberg, Ont., less than an hour north of Toronto. The assurance is that Batch No. 2 will be made from a different cereal and so will be vastly different. I fully expect it to be so and I can’t wait to try it.

But meanwhile we have this one – available at the LCBO, I might add, for $39.50. I’m just pouring the last of the bottle into my glass as I type. By now I know what to expect. I still think it deserves to be called whisky – though moonshine is a more beautiful word. Perhaps someone versant in the languages of the agricultural first peoples of this continent could find a name that means the bountiful personality of the life-giving grain. Though, come to think of it, I don’t believe wheat is native to North America. Please correct me if I’m wrong.

What does it taste like? I prefer it neat, even at 50%. It smells pungently granular, like a prairie silo after harvest, with touches of ripe, malty sweetness impinging, and a hint of flowers. But the taste!? Wheat has a sharp, bitter edge to it compared with the easy-going, half-wit-smiling sweetness of corn or the spicy, tight-lipped sarcasm of rye or the fruity chuckle of malted barley. Expect pepper and fennel and a whiff of lemon peel. A sudden glimpse of the heart of darkness. But it’s gone in a flash because this is pure spirit and without the sumptuous velvet and silk robes that long aging in oak imparts to the flavour and which linger on the palate, sometimes for hours, the effect of this whisky is momentary. Ariel rather than Caliban. Not so much a spirit as a sprite, naked and off about its business before you can blink.

And now the jug is empty.